Functional Reactive Programming

32 min read

Learning Outcomes

- Understand that the ObservableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming. construct of FunctionalFunctional languages are built around the concept of composable functions. Such languages support higher-order functions which can take other functions as arguments or return new functions as their result, following the rules of the Lambda Calculus. Reactive Programming is just another container of elements, but whose “push-based” architecture allows them to be used to capture asynchronousOperations that occur independently of the main program flow, allowing the program to continue executing while waiting for the operation to complete. behaviour

- Understand that ObservablesA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming. provide the benefits of functionalFunctional languages are built around the concept of composable functions. Such languages support higher-order functions which can take other functions as arguments or return new functions as their result, following the rules of the Lambda Calculus. programming: composability, reusability

- See that ObservablesA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming. structure complex stateful programs in a more linear and understandable way that maps more easily to the underlying state machine

- Use ObservablesA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming. to create simple UI programs in-place of asynchronousOperations that occur independently of the main program flow, allowing the program to continue executing while waiting for the operation to complete. event handling

Introduction

FunctionalFunctional languages are built around the concept of composable functions. Such languages support higher-order functions which can take other functions as arguments or return new functions as their result, following the rules of the Lambda Calculus. Reactive Programming describes an approach to modelling complex, asynchronousOperations that occur independently of the main program flow, allowing the program to continue executing while waiting for the operation to complete. behaviours that uses many of the functionalFunctional languages are built around the concept of composable functions. Such languages support higher-order functions which can take other functions as arguments or return new functions as their result, following the rules of the Lambda Calculus. programming principles we have already explored. In particular:

- Applications of functions to elements of containers to transform to a new container (e.g. map, filter, reduce etc. over arrays).

- Use of function composition and higher-order functionsA function that takes other functions as arguments or returns a function as its result. to define complex transformations from simple, reusable function elements.

We will explore FRP through an implementation of the ObservableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming. data structure in the Reactive Extensions for JavaScript (RxJS) library. We will then see it applied in application to a straightforward browser-based user interfaceA TypeScript construct that defines the shape of an object, specifying the types of its properties and methods. problem.

To support the code examples, the streams are visualised using rxviz.

Observable Streams

We have seen a number of different ways of wrapping collections of things in containers: built-in JavaScript arrays, linked-list data structures, and also lazy sequences. Now we’ll see that ObservableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming. is just another type of container with some simple examples, before demonstrating that it also easily applies to asynchronousOperations that occur independently of the main program flow, allowing the program to continue executing while waiting for the operation to complete. streams.

You can also play with a live version of this code. Note that the code in this live version begins with a pair of import statements, bringing the set of functions that we describe below into scope for this file from the rxjs libraries:

import { of, range, fromEvent, zip, merge, last, filter, scan, map, mergeMap, take, takeUntil } from 'rxjs';

Conceptually, the ObservableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

data structure just wraps a collection of things in a container in a similar way to the data structures we have seen before.

The function of creates an ObservableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

that will emit the specified elements in its parameter list in order. However, nothing actually happens until we initialise the stream. We do this by “subscribing” to the ObservableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

, passing in an “effectful” function that is applied to each of the elements in the stream. For example, we could print the elements out with console.log:

of(1,2,3,4)

.subscribe(console.log)

1

2

3

4

The requirement to invoke subscribe before anything is produced by the ObservableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

is conceptually similar to the lazy sequence, where nothing happened until we started calling next. But there is also a difference.

You could think of our lazy sequences as being “pull-based” data structures, because we had to “pull” the values out one at a time by calling the next function as many times as we wanted elements of the list. ObservablesA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

are a bit different. They are used to handle “streams” of things, such as asynchronousOperations that occur independently of the main program flow, allowing the program to continue executing while waiting for the operation to complete.

UI (e.g. mouse clicks on an element of a web page) or communication events (e.g. responses from a web service). These things are asynchronousOperations that occur independently of the main program flow, allowing the program to continue executing while waiting for the operation to complete.

in the sense that we do not know when they will occur.

Just as we have done for various data structures (arrays and so on) in previous chapters, we can define a transform over an ObservableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

to create a new ObservableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

. This transformation may have multiple steps the same way that we chained filter and map operations over arrays previously. In RxJS’s ObservableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

implementation, however, they’ve gone a little bit more functionalFunctional languages are built around the concept of composable functions. Such languages support higher-order functions which can take other functions as arguments or return new functions as their result, following the rules of the Lambda Calculus.

, by insisting that such operations are composed (rather than chained) inside a pipe. For example, here’s the squares of even numbers in the range [0,10):

const isEven = x => x%2 === 0,

square = x => x*x

range(10)

.pipe(

filter(isEven),

map(square)

)

.subscribe(console.log)

0

4

16

36

64

The three animations represent the creation (range) and the two transformations (filter and map), respectively.

We can relate this to similar operations on arrays which we have seen before:

const range = n => Array(n).fill().map((_, i) => i)

range(10)

.filter(isEven)

.map(square)

.forEach(console.log)

To solve the first Project Euler problem using RxJS, we generate a sequence of numbers from 0 to 999 with range(1000). We then use the filter operator to select numbers divisible by 3 or 5. We then use he scan operator, akin to reduce, accumulates the sum of these filtered numbers over time, and the last operator emits only the final accumulated sum. Finally, we subscribe to the observableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

and log the result to the console. Here’s the complete code:

range(1000)

.pipe(

filter(x => x%3 === 0 || x%5 === 0),

scan((a,v) => a+v),

last()

)

.subscribe(console.log);

In the developer console, only one number will be printed:

233168

We can see the values changes as they move further and further down the stream. The four animations represent the creation (range) and the three transformations (filter, scan and last), respectively. The last animation is empty, since we only emit the last value, which will be off screen.

Scan is very much like the reduce function on Array in that it applies an accumulator function to the elements coming through the ObservableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

, except instead of just outputting a single value (as reduce does), it emits a stream of the running accumulation (in this case, the sum so far). Thus, we use the last function to produce an ObservableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

with just the final value.

There are also functions for combining ObservableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

streams. The zip function lets you pair the values from two streams into an array:

const

columns = of('A','B','C'),

rows = range(3);

zip(columns,rows)

.subscribe(console.log)

[“A”,0]

[“B”,1]

[“C”,2]

If you like mathy vector speak, you can think of the above as an inner product of the two streams.

By contrast, the mergeMap operator gives the Cartesian product of two streams. That is, it gives us a way to take, for every element of a stream, a whole other stream, but flattened (or projected) together with the parent stream. The following enumerates all the row/column indices of cells in a spreadsheet:

columns.pipe(

mergeMap(column => rows.pipe(

map(row => [column, row])

))

).subscribe(console.log)

[“A”, 0]

[“A”, 1]

[“A”, 2]

[“B”, 0]

[“B”, 1]

[“B”, 2]

[“C”, 0]

[“C”, 1]

[“C”, 2]

If we contrast mergeMap and map, map will produce an ObservableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

of ObservablesA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

, while mergeMap will produce a single stream with all of the values. Contrast the animation for map with the previous mergeMap animation. map has three separate branches, where each one represents its own observableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

stream. The output of the console.log is an instance of the ObservableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

class itself, which is not very useful!

columns.pipe(

map(column => rows.pipe(

map(row => [column, row])

))

).subscribe(console.log)

Observable

Observable

Observable

Another way to combine streams is merge. Streams that are generated with of and range have all their elements available immediately, so the result of a merge is not very interesting, just the elements of one followed by the elements of the other:

merge(columns,rows)

.subscribe(console.log)

A

B

C

0

1

2

However, merge when applied to asynchronousOperations that occur independently of the main program flow, allowing the program to continue executing while waiting for the operation to complete.

streams will merge the elements in the order that they arrive in the stream. For example, a stream of key-down and mouse-down events from a web-page:

const

key$ = fromEvent<KeyboardEvent>(document,"keydown"),

mouse$ = fromEvent<MouseEvent>(document,"mousedown");

It’s a convention to end variable names referring to ObservableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

streams with a $ (I like to think it’s short for “$tream”, or implies a plurality of the things in the stream, or maybe it’s just because cash rules everything around me).

We can analogously think of mouse$ as an array of MouseEvent objects, e.g., [MouseEvent, MouseEvent, MouseEvent, MouseEvent, MouseEvent], and then we can perform operations on this array just as we would with a typical array of values. However, rather than being a fixed array of MouseEvent, they are an ongoing stream of MouseEvent objects that occur over time. Therefore, instead of being a static collection of events that you can iterate over all at once, the ObservableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

mouse$ represents a dynamic, potentially infinite sequence of events that are emitted as they happen in real-time.

The following lets us see in the console the keys pressed as they come in, it will keep running for as long as the web page is open:

key$.pipe(

map(e => e.key)

).subscribe(console.log)

The animation displays the stream as the user types in the best FIT unit in to the webpage:

The following prints “!!” on every mousedown:

mouse$.pipe(

map(_ => "!!")

).subscribe(console.log)

The yellow highlight signifies when the mouse is clicked!

Once again this will keep producing the message for every mouse click for as long as the page is open. Note that the subscribes do not “block”, so the above two subscriptions will run in parallel. That is, we will receive messages on the console for either key or mouse downs whenever they occur.

The following achieves the same thing with a single subscription using merge:

merge(key$.pipe(map(e => e.key)),

mouse$.pipe(map(_ => "!!"))

).subscribe(console.log)

Observable Cheatsheet

The following is a very small (but sufficiently useful) subset of the functionality available for RxJS. I’ve simplified the types rather greatly for readability and not always included all the optional arguments.

Creation

The following functions create ObservableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming. streams from various sources.

// produces the list of arguments as elements of the stream

of<T>(...args: T[]): Observable<T>

// produces a stream of numbers from “start” until “count” been emitted

range(start?: number, count?: number): Observable<number>

// produces a stream for the specified event, element type depends on

// event type and should be specified by the type parameter, e.g.: MouseEvent, KeyboardEvent

fromEvent<T>(target: FromEventTarget<T>, eventName: string): Observable<T>

// produces a stream of increasing numbers, emitted every “period” milliseconds

// emits the first event immediately

interval(period?: number): Observable<number>

// after given initial delay, emit numbers in sequence every specified duration

timer(initialDelay: number, period?: number): Observable<number>

Combination

Creating new ObservableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming. streams from existing streams

// create a new Observable stream from the merge of multiple Observable streams.

// The resulting stream will have elements of Union type.

// i.e. the type of the elements will be the Union of the types of each of the merged streams

// Note: there is also an operator version.

merge<T, U...>(t: Observable<T>, u: Observable<U>, ...): Observable<T | U | ...>

// create n-ary tuples (arrays) of the elements at the head of each of the incoming streams

zip<T, U...>(t: Observable<T>, r: Observable<U>): Observable<[T, U, ...]>

Observable methods

Methods on the ObservableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming. object itself that may be chained.

// composes together a sequence of operators (see below) that are applied to transform the stream

pipe<A>(...op1: OperatorFunction<T, A>): Observable<A>;

// {next} is a function applied to each element of the stream

// {error} is a function applied in case of error (only really applicable for communications)

// {complete} is a function applied on completion of the stream (e.g. cleanup)

// @return {Subscription} returns an object whose “unsubscribe” method may be called to cleanup

// e.g. unsubscribe could be called to cancel an ongoing Observable

subscribe(next?: (value: T) => void, error?: (error: any) => void, complete?: () => void): Subscription;

Operators

Operators are passed to pipe. They all return an OperatorFunction which is used by pipe.

// transform the elements of the input stream using the “project” function

map<T, R>(project: (value: T) => R)

// only take elements which satisfy the predicate

filter<T>(predicate: (value: T) => boolean)

// take “n” elements

take<T>(n: number)

// take the last element

last<T>()

// AKA flatMap: produces an Observable<R> for every input stream element T

mergeMap<T, R>(project: (value: T) => Observable<R>)

// accumulates values from the stream

scan<T, R>(accumulator: (acc: R, value: T) => R, seed?: R)

// push an arbitrary object on to the start/end of the stream

startWith<T>(o: T)

endWith<T>(o: T)

A User Interface Example

Modern computer systems often have to deal with asynchronousOperations that occur independently of the main program flow, allowing the program to continue executing while waiting for the operation to complete. processing. Examples abound:

- In RESTful web services, where a client sends a non-blocking request (e.g. GET) with no guarantee of when the server will send a response.

- In user interfacesA TypeScript construct that defines the shape of an object, specifying the types of its properties and methods. , events are triggered by user interaction with different parts of the interfaceA TypeScript construct that defines the shape of an object, specifying the types of its properties and methods. , which may happen at any time.

- Robotics and other systems with sensors, the system must respond to events in the world.

Under the hood, most of these systems work on an event model, a kind of single-threaded multitasking where the program (after initialisation) polls a FIFO (First-In-First-Out) queue for incoming events in the so-called event loop. When an event is popped from the queue, any subscribed actions for the event will be applied.

In JavaScript the first event loop you are likely to encounter is the browser’s. Every object in the DOM (Document Object Model - the tree data structure behind every webpage) has events that can be subscribed to, by passing in a callbackA function passed as an argument to another function, to be executed after some event or action has occurred. function which implements the desired action. We saw a basic click handler earlier.

Handling a single event in such a way is pretty straightforward. Difficulties arise when events have to be nested to handle a (potentially bifurcating) sequence of possible events.

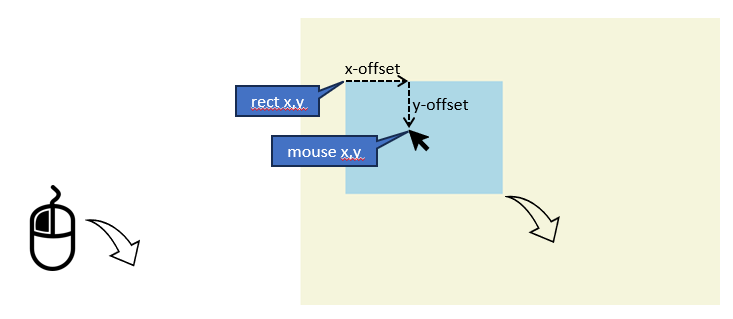

A simple example that begins to show the problem is implementing a UI to allow a user to drag an object on (e.g.) an SVGScalable Vector Graphics - another part of the HTML standard for specifying images declaratively as sets of shapes and paths. canvas (play with it here!). We illustrate the desired behaviour below. When the user presses and holds the left mouse button we need to initiate dragging of the blue rectangle. The rectangle should move with the mouse cursor such that the x and y offsets of the cursor position from the top-left corner of the rectangle remain constant.

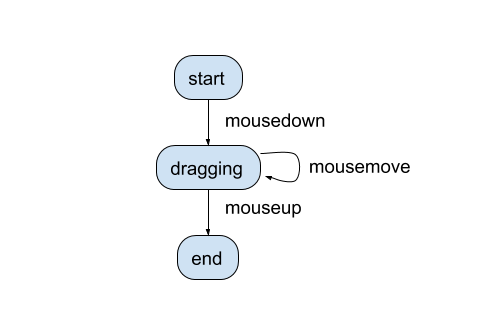

The state machine that models this behaviour is pretty simple:

There are only three transitions, each triggered by an event.

Turning a State-Machine into Code with Event Listeners

The typical way to add interaction to web-pages and other UIs has historically been by adding Event Listeners to the UI elements for which we want interactive behaviour. In software engineering terms it’s typically referred to as the Observer Pattern (not to be confused with the “ObservableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming. ” FRP abstraction we have been discussing).

Here’s an event-driven code fragment that provides such dragging for some SVGScalable Vector Graphics - another part of the HTML standard for specifying images declaratively as sets of shapes and paths.

element draggableRect that is a child of an SVGScalable Vector Graphics - another part of the HTML standard for specifying images declaratively as sets of shapes and paths.

canvas element referred to by the variable svg:

const svg = document.getElementById("svgCanvas")!;

const rect = document.getElementById("draggableRect")!;

rect.addEventListener('mousedown', e => {

const

xOffset = Number(rect.getAttribute('x')) - e.clientX,

yOffset = Number(rect.getAttribute('y')) - e.clientY,

moveListener = (e:MouseEvent) => {

rect.setAttribute('x', String(e.clientX + xOffset));

rect.setAttribute('y', String(e.clientY + yOffset));

},

done = () => {

svg.removeEventListener('mousemove', moveListener);

};

svg.addEventListener('mousemove', moveListener);

svg.addEventListener('mouseup', done);

})

We add “event listeners” to the HTMLHyper-Text Markup Language - the declarative language for specifying web page content.

elements, which invoke the specified functions when the event fires. There are some awkward dependencies. The moveListener function needs access to the mouse coordinates from the mousedown event, the done function which ends the drag on a mouseup event needs a reference to the moveListener function so that it can clean it up.

It’s all a bit amorphous:

- the flow of control is not very linear or clear;

- we’re declaring callbackA function passed as an argument to another function, to be executed after some event or action has occurred. functions inside of callbackA function passed as an argument to another function, to be executed after some event or action has occurred. functions and the side effect of the program (that is, the change of state to the underlying web page by moving the rectangle) is hidden in the deepest nested part of the program;

- we have to manually unsubscribe from events when we’re done with them by calling

removeEventListener(or potentially deal with weird behaviour when unwanted zombie events fire).

The last issue is not unlike the kind of resource cleanup that RAII is meant to deal with.

Generally speaking, nothing about this function resembles the state machine diagram.

The code sequencing has little sensible flow. The problem gets a lot worse in highly interactive web pages with lots of different possible interactions all requiring their own event handlers and cleanup code.

Impure FRP Solution

We now rewrite precisely the same behaviour using ObservableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming. FRP:

const svg = document.getElementById("svgCanvas")!;

const rect = document.getElementById("draggableRect")!;

const mousedown = fromEvent<MouseEvent>(rect,'mousedown'),

mousemove = fromEvent<MouseEvent>(svg,'mousemove'),

mouseup = fromEvent<MouseEvent>(svg,'mouseup');

mousedown

.pipe(

map(({clientX, clientY}) => ({

mouseDownXOffset: Number(rect.getAttribute('x')) - clientX, // <-\

mouseDownYOffset: Number(rect.getAttribute('y')) - clientY // <-|

})), // D

mergeMap(({mouseDownXOffset, mouseDownYOffset}) => // E

mousemove // P

.pipe( // E

takeUntil(mouseup), // N

map(({clientX, clientY}) => ({ // D

x: clientX + mouseDownXOffset, // E

y: clientY + mouseDownYOffset // N

}))))) // C

.subscribe(({x, y}) => { // Y

rect.setAttribute('x', String(x)) // >-----------------------------|

rect.setAttribute('y', String(y)) // >-----------------------------/

});

The ObservableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming. ’s mousedown, mousemove and mouseup are like streams which we can transform with familiar operators like map and takeUntil. The mergeMap operator “flattens” the inner mousemove ObservableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming. stream back to the top level, then subscribe will apply a final action before doing whatever cleanup is necessary for the stream.

Compared to our state machine diagram above:

- we have modelled each of the possible transition triggers as streams;

- the flow of data is from top to bottom, with the cycling branch handled by the mergeMap operation;

- the only side effectsAny state change that occurs outside of a function’s local environment or any observable interaction with the outside world, such as modifying a global variable, writing to a file, or printing to a console. (the movement of the rectangle) occur in the function passed to the subscribe;

- the cleanup of subscriptions to the mousemove and mouseup events is handled automatically by the

takeUntilfunction when it closes the streams.

However, there is still something not very elegant about this version. As indicated by my crude ASCII art in the comment above, there is a dependency in the function applied to the stream by the first map, on the DOM element being repositioned in the function applied by subscribe. This dependency on mutable state outside the function scope makes this solution impure.

Pure FRP Solution

We can remove this dependency on mutable state, making our event stream a pure “closed system”, by introducing a scan operator on the stream to accumulate the state using a pure functionA function that always produces the same output for the same input and has no side effects.

.

First, let’s define a type for the state that will be accumulated by the scan operator. We are concerned with

the position of the top-left corner of the rectangle, and (optionally, since it’s only relevant during mouse-down dragging) the offset of the click position from the top-left of the rectangle:

type State = Readonly<{

pos: Point,

offset?: Point

}>

We’ll introduce some types to model the objects coming through the stream and the effects they have when applied to a State object in the scan. First, all the events we care about have a position on the SVGScalable Vector Graphics - another part of the HTML standard for specifying images declaratively as sets of shapes and paths.

canvas associated with them, so we’ll have a simple immutable Point interfaceA TypeScript construct that defines the shape of an object, specifying the types of its properties and methods.

with x and y positions and a couple of handy vector math methods (note that these create a new Point rather than mutating any existing state within the Point):

class Point {

constructor(public readonly x: number, public readonly y: number) {}

add(p: Point) { return new Point(this.x + p.x,this.y + p.y) }

sub(p: Point) { return new Point(this.x - p.x,this.y - p.y) }

}

Now we create a subclass of Point with a constructor letting us instantiate it for a given (DOM) MouseEvent and an abstract (placeholder) definition for a function to apply the correct update action to the State:

abstract class MousePosEvent extends Point {

constructor(e: MouseEvent) { super(e.clientX, e.clientY) }

abstract apply(s: State): State;

}

And now two further subclasses with concrete definitions for apply.

class DownEvent extends MousePosEvent {

apply(s: State) { return { pos: s.pos, offset: s.pos.sub(this) } }

}

class DragEvent extends MousePosEvent {

apply(s: State) { return { pos: this.add(s.offset), offset: s.offset } }

}

Setup of the streams is as before:

const svg = document.getElementById("svgCanvas")!,

rect = document.getElementById("draggableRect")!,

mousedown = fromEvent<MouseEvent>(rect,'mousedown'),

mousemove = fromEvent<MouseEvent>(svg,'mousemove'),

mouseup = fromEvent<MouseEvent>(svg,'mouseup');

But now we’ll capture initial position of the rectangle one time only in an immutable Point object outside of the stream logic.

const initialState: State = {

pos: new Point(

Number(rect.getAttribute('x')),

Number(rect.getAttribute('y'))

)

}

Now we will be able to implement the ObservableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

stream logic, using a function passed to scan to manage state.

Since we use only pure functionsA function that always produces the same output for the same input and has no side effects.

we have a strong guarantee that the logic is self-contained, with no dependency on the state of the outside world!

mousedown

.pipe(

mergeMap(mouseDownEvent =>

mousemove.pipe(

takeUntil(mouseup),

map(mouseDragEvent => new DragEvent(mouseDragEvent)),

startWith(new DownEvent(mouseDownEvent)))),

scan(

(s: State, e: MousePosEvent) => e.apply(s),

initialState))

.subscribe(e => {

rect.setAttribute('x', String(e.rect.x))

rect.setAttribute('y', String(e.rect.y))

});

Note that inside the mergeMap we use the startWith operator to force a DownEvent onto the start of the flattened stream. Then the accumulator function passed to scan uses subtype polymorphism to cause the correct behaviour for the different types of MousePosEvent`.

The advantage of this code is not brevity; with the introduced type definitions it’s longer than the previous implementations of the same logic. Rather, the advantages of this pattern are:

- maintainability: we have separated setup code and state management code and importantly, separate the side effectsAny state change that occurs outside of a function’s local environment or any observable interaction with the outside world, such as modifying a global variable, writing to a file, or printing to a console.

to only be in

subscribe; - scalability: we can extend this code pattern to handle more complicated state machines. We can easily

mergein more input streams, adding Event types to handle theirStateupdates, and the only place we have to worry about effects visible to the outside world is in the function passed tosubscribe.

As an example of scalability we will be using this same pattern to implement the logic of an asteroids arcade game in the next chapter.

MergeMap vs SwitchMap vs ConcatMap

In RxJS, mergeMap, switchMap, and concatMap are operators used for transforming and flattening observablesA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

. Each has its own specific behaviour in terms of how it handles incoming values and the resulting observableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

streams. Here’s a breakdown of each:

Let’s consider three almost identical pieces of code

fromEvent(document, "mousedown").pipe(mergeMap(() => interval(200)))

fromEvent(document, "mousedown").pipe(switchMap(() => interval(200)))

fromEvent(document, "mousedown").pipe(concatMap(() => interval(200)))

With mergeMap, each mousedown event triggers a new interval(200) observableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

. All these interval observablesA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

will run concurrently, meaning their emitted values will interleave in the output. In the animation, the x2 occurs when two observablesA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

emit at approximately the same time, and the values overlap too much to show separately.

With switchMap, each time a mousedown event occurs, it triggers an interval(200) observableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

. If another mousedown event occurs before the interval observableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

finishes (interval doesn’t finish on its own), the previous interval observableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

is canceled, and a new one begins. This means only the most recent mousedown event’s observableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

is active. This can be seen as the counter restarting every single time a click occurs (remember interval emits sequential numbers).

With concatMap, each time a mousedown event occurs, it starts emitting values from the interval(200) observableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

. Importantly, if a second mousedown event occurs while the previous interval observableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

is still emitting, the new interval won’t start until the previous one has completed. However, since interval is a never-ending observableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

, in practice, each mousedown event’s observableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.

will queue up and only start after the previous ones are manually stopped or canceled. Therefore, no matter how many times a click occurs, the next interval will never begin.

We can make an adjustment to this, where, we stop the interval after four items.

fromEvent(document, "mousedown").pipe(concatMap(() => interval(200).pipe(take(4))))

Unlike the previous example with a never-ending interval, in this case, each interval observableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming. completes after emitting four values, so the next mousedown event’s observableA data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming. will queue up and start automatically as soon as the previous one completes. This setup ensures that each click’s sequence of interval emissions will be handled one after the other, with no overlap, maintaining the order of clicks and processing each one to completion before starting the next.

Glossary

Asynchronous: Operations that occur independently of the main program flow, allowing the program to continue executing while waiting for the operation to complete.

Functional Reactive Programming (FRP): A programming paradigm that combines functional and reactive programming to handle asynchronous data streams and event-driven systems.

Observable: A data structure that represents a collection of future values or events, allowing for asynchronous data handling and reactive programming.